On the paths of war by Hektor Dule

Rather than give my own interpretation of this statue I thought to reproduce the article below which includes a number of interpretations of the statue of the Partisan and the women offering him a refreshing drink. It originally appeared as Eros on the Roads of War: Some Brief Notes on Hektor Dule’s Në Udhët e Luftës For and Against the Decadences of the Fles by Raino Isto

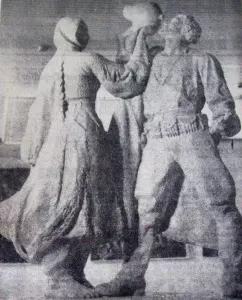

First exhibited in during the National Exhibition dedicated to the 30th Anniversary of National Liberation, Hektor Dule’s Në Udhët e Luftës [On the Paths of War] (also called Në Rrugën e Luftës) now stands in Tirana’s Great Park,[1] near to the fountains (and also to the new assortment of exercise equipment installed in the last few years). The bronze statue, depicting an Albanian woman holding up a jug of water and allowing a partisan soldier to drink deeply from it, seems appropriately placed in its pseudo-natural surroundings. It is, after all, about the nourishment of the body in the course of its struggles…what better location for it that the Great Park, where the body—in exercise, in sex, in relaxation and communion with an artificial nature—is fundamental to the creation and experience of space?

In 1975, writing of the work’s appearance in the exhibition (in its earlier version done in plaster), Fatmir Haxhiu wrote that ‘precisely in this moment both ordinary and life-affirming, in this fundamentally simple act—one that may people have encountered during the war years (a mother giving a jug of water to a partisan)—the artist struggles to show the love and intimacy that our people felt for the partisans, and the support that ordinary people gave to the partisans during the National Liberation War. And the artist achieves his goal. The two figures are connected to each other in a conceptual unity and by the complete harmonization of their forms.’[2] Later, Haxhiu writes, ‘It is an intimate work’ [my emphasis].[3] The remainder of his article praises Dule (who at this point was one of the important figures in a new generation of Albanian sculptors, best known for the Mushqeta monument and his work with the famous ‘monumental trio’ of K. Rama, Sh. Hadëri, and M. Dhrami), offers the typically supportive assessment of his treatment of themes from the National Liberation War, and makes some minor aesthetic criticisms aimed at his future improvement as a sculptor.

Without dismissing the relevance of the ever-present theme of the partisan struggle, and certainly without wishing to poke fun at either Haxhiu’s analysis or Dule’s work, I would like to suggest a slightly different interpretation of Në Udhët e Luftës. Perhaps it is more accurate to say: I wish to expand upon our understanding of the themes of the partisan struggle precisely by pausing as we read the words love and intimacy, and considering what sculptural traditions Dule’s work is truly in dialogue with. In short, I would like to introduce (or perhaps, since so much popular discourse seems so committed to separating the two, to reintroduce) the question of the body, sensuality, and sex into the discussion of Albanian socialist realist sculpture.

For it seems undeniable to me that Dule’s sculptural group carries an immense sexual charge (and not just because of some vague associations with what goes on elsewhere in the Great Park). If Haxhiu’s analysis of the work seems to avoid this aspect, I think the fact that he uses the words ‘love and intimacy’ to characterize the work indicates his awareness of the issues potentially broached by the work and an active attempt to undercut them. In much the same way, I think that Dule is trying to use the tropes of a certain sculptural tradition in the context of socialist realism in order partially to undermine them and partially to harness them.

To see the eroticism of Dule’s sculpture, we need only compare it to a work that I dare say it was actually intended to be in dialogue with: Clodion’s Nymph and Satyr Carousing (also known as The Intoxication of Wine), 18th century (ca. 1780–90), terracotta, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Clodion’s work, which straddles (as the sculptor himself did) the turn towards the Neoclassical in sculpture with the more playful sensuality of the Rococo, is a kind of decadent mirror of Dule’s work. In Clodion: a satyr, the preeminent mythical being of male lust, leans back, allowing himself to rest upon a stone as he lifts one animal leg off the ground and pulls a naked nymph to him, his fingers digging into the flesh of her back. She leans into him, straddling his left leg, wrapping her right arm around his neck, and holds a goblet of wine above his mouth, pouring. In Dule: an Albanian woman, barefoot and dressed in garb that suggests she must be a villager) stands before a male partisan. Her feet are slightly apart, and one of his booted feet steps forward, placed firmly between hers. Her left arm and shoulder are drawn back, her clothing flowing out a bit behind her, and her right hand reaches out to steady a full, rounded jug as the partisan holds it in his right hand, by its handle, above his head. His head is thrown back, the jug held a few inches from his open mouth to allow the water to flow down his throat. His left shoulder is likewise thrown back, exposing his chest, and he braces his weight on his left leg. His left hand steadies his rifle at waist height, as its barrel juts out phallically, but directed away from the woman. The only contact between the two bodies takes place between her sleeve and his chest as she steadies the jug, but she stares directly at his face as he drinks in a fixed gaze that connects the two emotionally, physically, and compositionally. Like Clodion’s pair, Në Udhët e Luftës rewards viewing in the round, shifting perspectives that give us different views of the two bodies and their intimate connections.

I do not think that Dule’s sculpture intends to posit for its viewer a narrative of sexual engagement between the village woman and the partisan he shows, although that is certainly possible.[4] Rather, I think that Dule takes the tradition of which Clodion is emblematic (a Neoclassical sensibility, but with one foot still in the aristocratic tastes of the Rococo,[5] celebrating not only the sobriety of antiquity but also its Bacchic excesses) and attempts to overcome it in the context of socialist realism. Socialist realism was, after all, as much a ‘logic of cultural supplementarity, a logic that established itself by qualifying previous aesthetic traditions that were already…known’ (as Devin Fore asserts), as it was a style in itself.[6] At the same time, however, he brings sensuality into socialist realism, offering a view of the National Liberation War—in its most ‘ordinary’ and ‘life-affirming’ moments—as a struggle that includes the sensual gratification of the body and its desires, of the partisan reinvigorated physically by his encounter with the village mother. There is no need to digress into Freud, and love, and the death drive (though indeed one could) to consider the equation of war, sexuality, and physical release that Në Udhët e Luftës presents. As much as Haxhiu seems careful to ensure that ‘love and intimacy’ have strictly Platonic meanings in the context of Dule’s sculptural pair, the suggestion of sexual fullness present in the jug, the rifle held stiffly at waist-level, the partisan’s head thrown back, and the assertive offering of the village woman trace the contours of a very different set of connotations.

One could certainly go further, and perhaps one should. All I mean to suggest here is the necessity of reasserting the body and its pleasures—sexual and sensual—at the heart of socialist realist sculpture (and art in general) in Albania (and elsewhere, of course). Works like Në Udhët e Luftës reveal the tension of inheriting the sculptural tradition of bodily desire made materially manifest, and the rich possibilities of bringing that ‘decadent’ tradition into the context of the National Liberation War narrative—of denying the pleasures of the flesh, but also of reaffirming them in the context of sacrifice and struggle. It should also remind us that the war years were not simply a clash of battalions and strategies, of ideas and ideologies, but also of bodies and their desires.

[1] I would welcome anyone with information about the precise year in which the bronze version of the statue was placed in the park—I confess I have no information regarding this placement.

[2] Fatmir Haxhiu, ‘Në Udhët e Luftës: Shënime rreth grupit skulptural të H. Dules,’ Drita, 28 September 1975.

[3] Ibid.

[4] And the narrative itself seems plausible, though I have read of no accounts that discuss the occurrence and/or frequency of sexual dalliances between partisans and the ‘ordinary people’ that gave them support and shelter during the war.

[5] Indeed, what style or period could more fully epitomize the ‘decadence’ of bourgeois culture—that perennial enemy of socialist society—than the Rococo?

[6] Devin Fore, Realism After Modernism: The Rehumanization of Art and Literature (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012), 244

Location

In the centre of Tirana Park.

GPS

41.31374401

19.81815702

DMS

41° 18′ 49.4784” N

19° 49′ 5.3653” E

Altitude

137.7 m