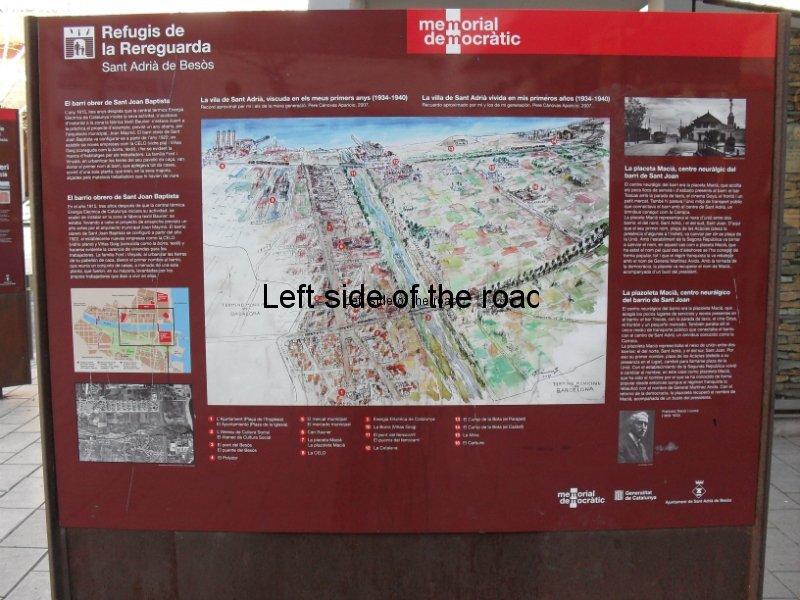

The air raid shelter of Placeta Macià, Sant Adrià de Besòs

The air raid shelter (refugi antiaeri) in Placeta Macià, Sant Adrià de Besòs, Barcelona, provides an insight to what life was like for ordinary, working class, people during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39.

Many thousands of visitors go to Barcelona each year but an increasing number of them are starting to go off the beaten track of the Rambla and the Gaudi buildings to explore some of the lest ‘touristy’ aspects of the city.

Of the hoards who walk down the bustling Rambla some might have read George Orwell’s depiction of the Spanish Civil War in his book Homage to Catalonia. Standing outside Café Moka they might imagine what it was like in the stand-off between two armies, on the same side, on the brink of their own ‘civil war’, occasionally taking pot shots at one another.

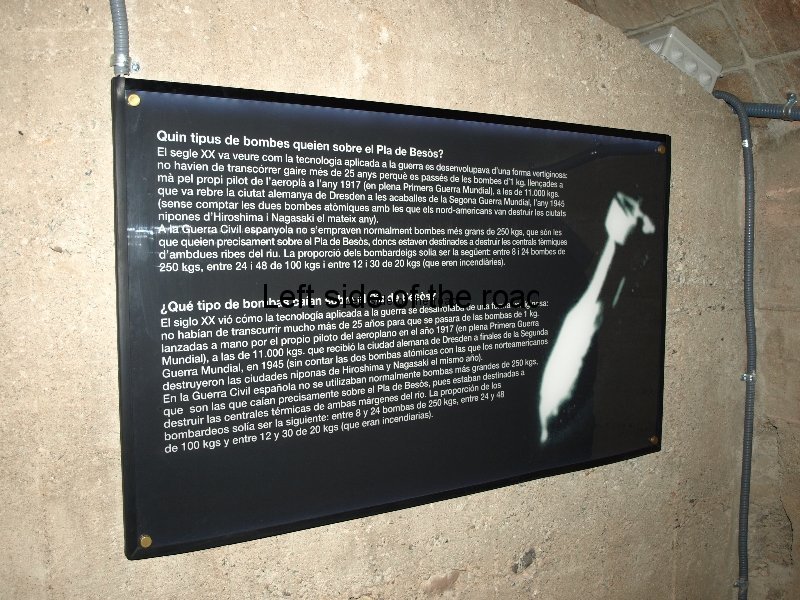

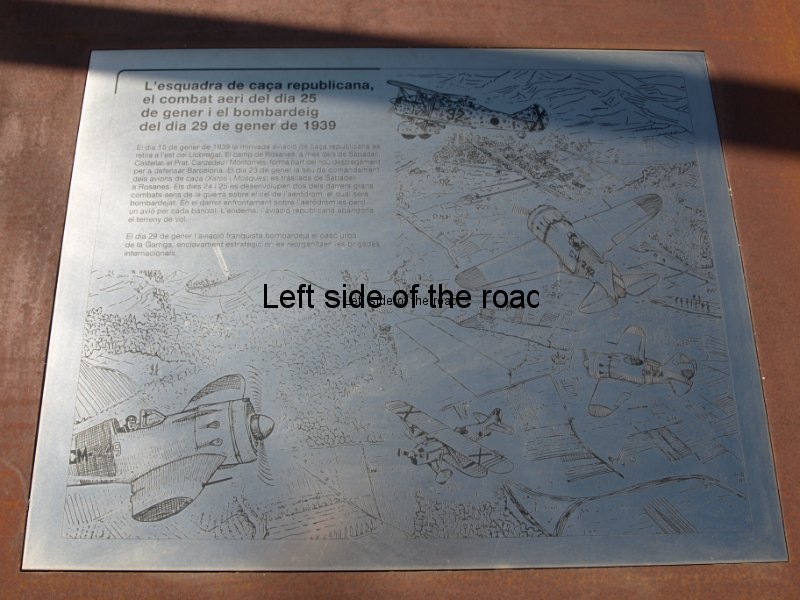

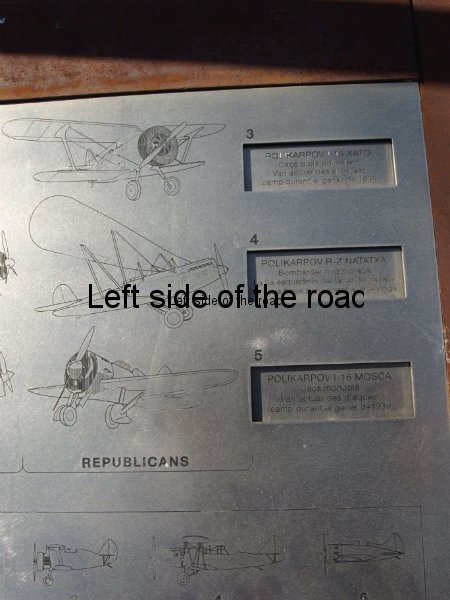

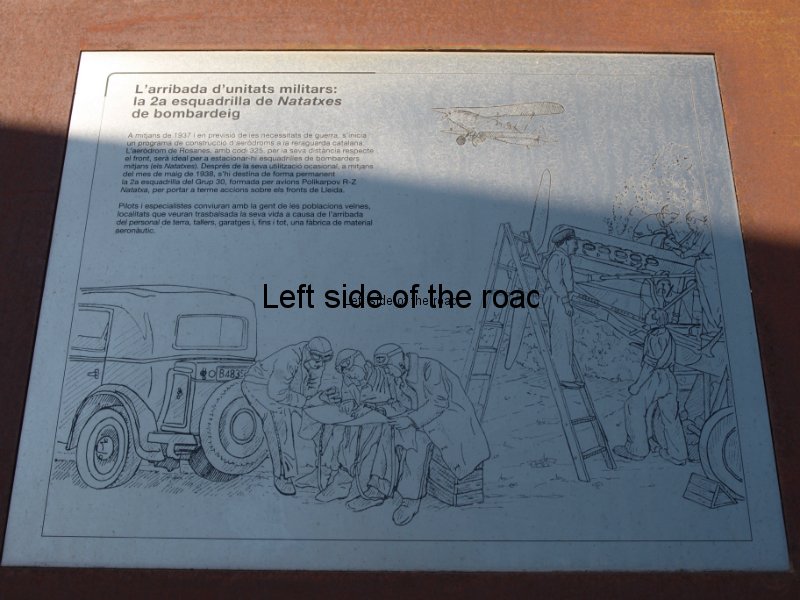

Orwell had the luxury, the wealth and the opportunity to get out of the country before Hitler and Mussolini’s aircraft, happily brought in on the side of the rebel Franco, started to regularly bombard this Republican city, using a strategy taken to an even higher level a few years later. That was the strategy of terrorising and punishing the civilian population with mass bombing and the destruction of their cities, as was seen in Warsaw, Liverpool and Leningrad, amongst many others.

As in those other cities the people of Barcelona didn’t just sit and wait for what was to rain down on them. If they could not fight at the front then they would construct shelters to protect themselves from the bombs and deny the enemy the satisfaction of their acquiescence and defeat. This form of passive resistance was evident in Barcelona and many other Catalan towns and cities.

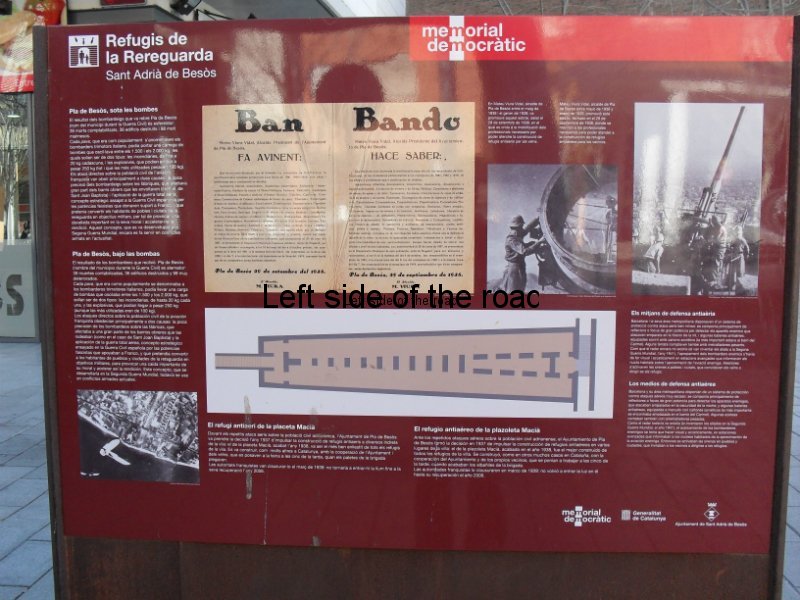

In the intervening years, since the end of the war in 1939, many of these air raid shelters have been bulldozed both to eliminate any popular memory of resistance and then later as the country started to develop and modernise after Franco’s death in 1975. However, since 2007, following a decision of the Generalitat (the Catalan government), much of what does remain is coming to light and is being made accessible to both local people and any visitors with an interest in an important and significant struggle in the middle years of the 20th century.

Those facets of war that might have been hidden are now being visited by an increasing number of people. In their visits they are offered the opportunity to consider the war in a different way from that presented on the big screen. This representation has evolved over the years from the morale boosting antics of Errol Flynn through the gung-ho approach of John Wayne to the more poignant aspect of war as depicted in Saving Private Ryan.

In Catalonia this unveiling of the past is part of a much bigger project, the first in Spain but part of a much wider, in fact worldwide, scheme called Democratic Memory. Of the more than 70 sites already on the list in Catalonia here I just want to talk about one of them, located in the working class district of Sant Adrià de Besòs, (easily reached via Metro L2 from the central cultural highlights of Barcelona), the air raid shelter in Placeta Macià.

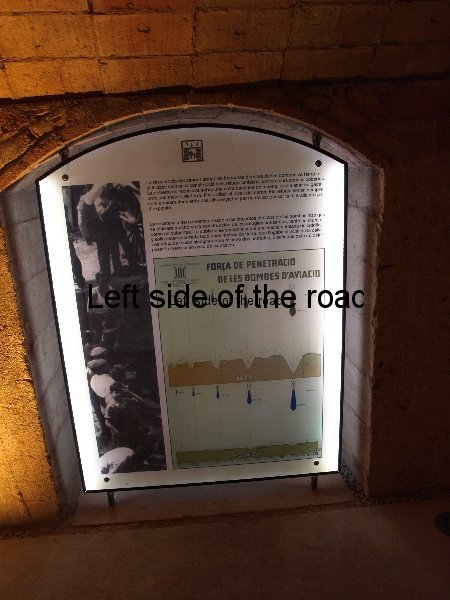

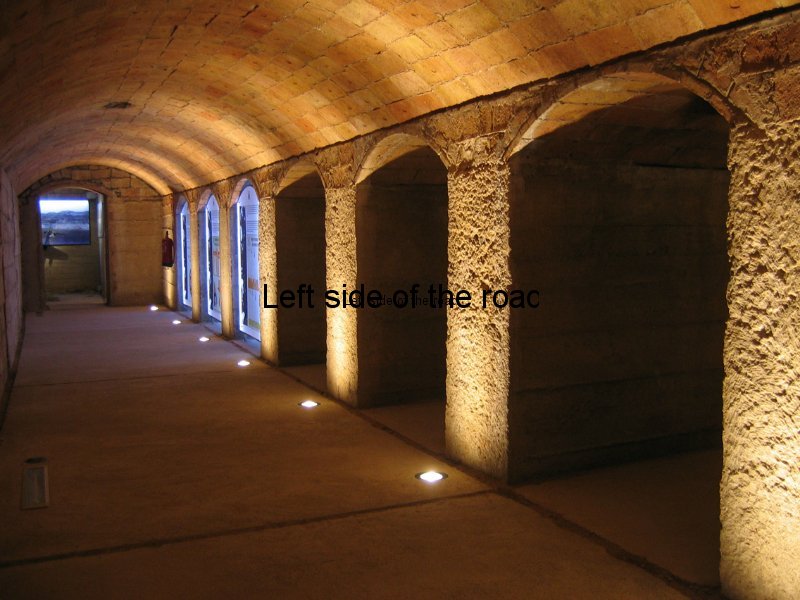

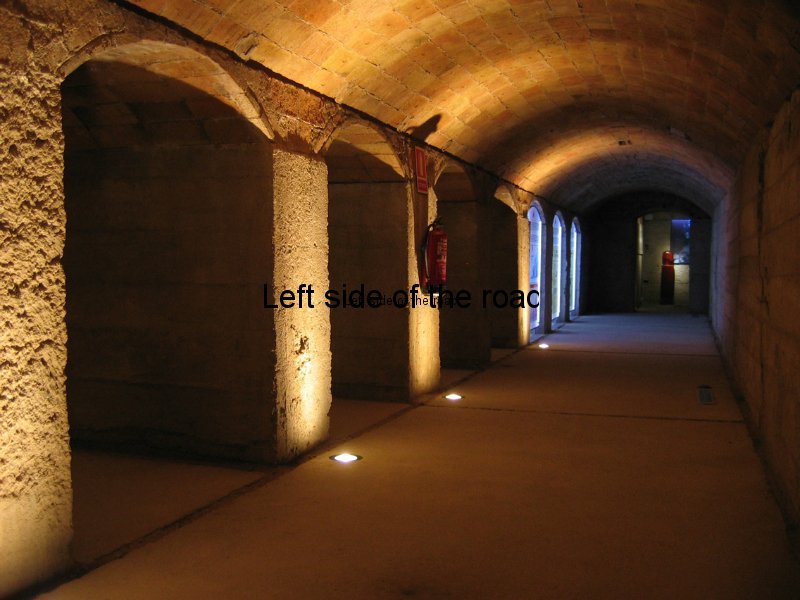

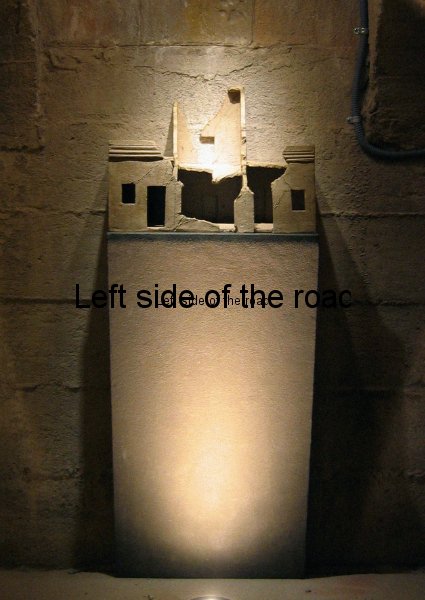

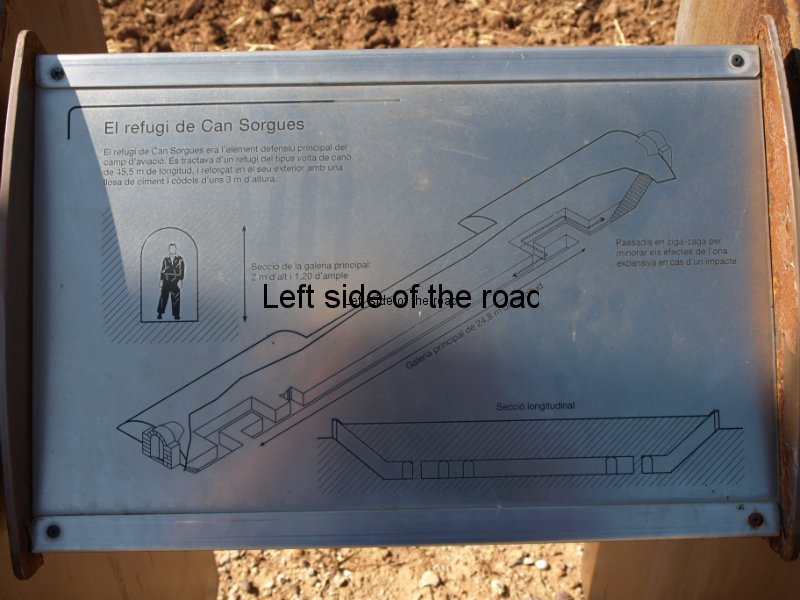

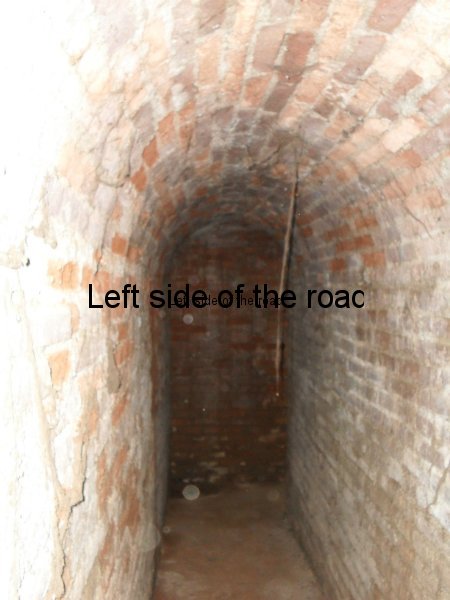

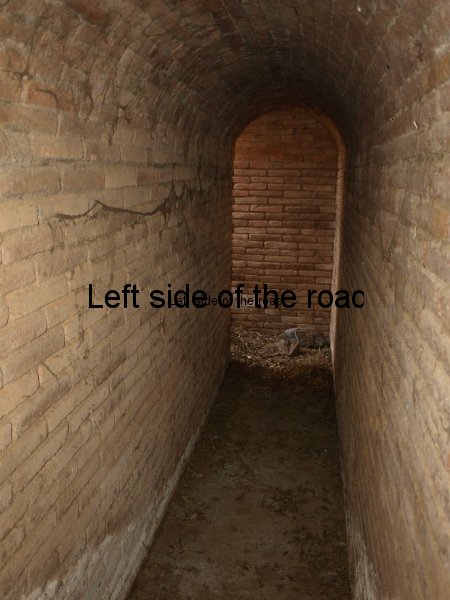

This is an impressive construction in its own right, especially taking into consideration the conditions under which it was built, and is the only one of the seven that originally existed in the district to have survived into the 21st century. Constructed in the shape of a rhomboid it has a central corridor with alcoves on either side and was built, in 1938, to provide shelter for up to 500 local people.

Although it is underground the aim of the cleaning and restoration has been to make it as accessible as possible. First, it is free to enter. ‘Why should those who built it, and their children and grandchildren, now be charged to visit it – 70 years after its construction,’ says Jordi Vilalta, the enthusiastic coordinator for the shelter. He is based in the Museu d’Història de la Immagració de Catalunya (itself one of the 71 sites) which is situated a short distance away on the opposite side of the River Besòs.

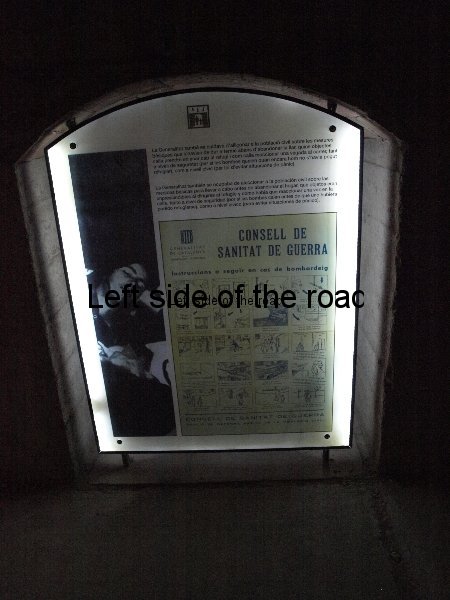

One of the aims of the project is to involve children in a conversation with the past of their families and so school visits are organised where those who were themselves school children in 1938 tell of their memories, experiences, fears and daily life in general during the relatively short, but incredibly intense, life of the shelter.

‘We have found it very difficult to find actual photos of people in the shelter’, continues Jordi, ‘but what we do have are some drawings made by children at the time. What we find fascinating is the fact that, apart from the ‘advances’ in aircraft and technology, these images are almost the same as those produced by children in the Palestinian city of Jenin in 2002.’

To encourage the involvement of the young in this small and intimate museum the visitors are encouraged to touch the exhibits and to try to understand the idea of destruction but without any images of death.

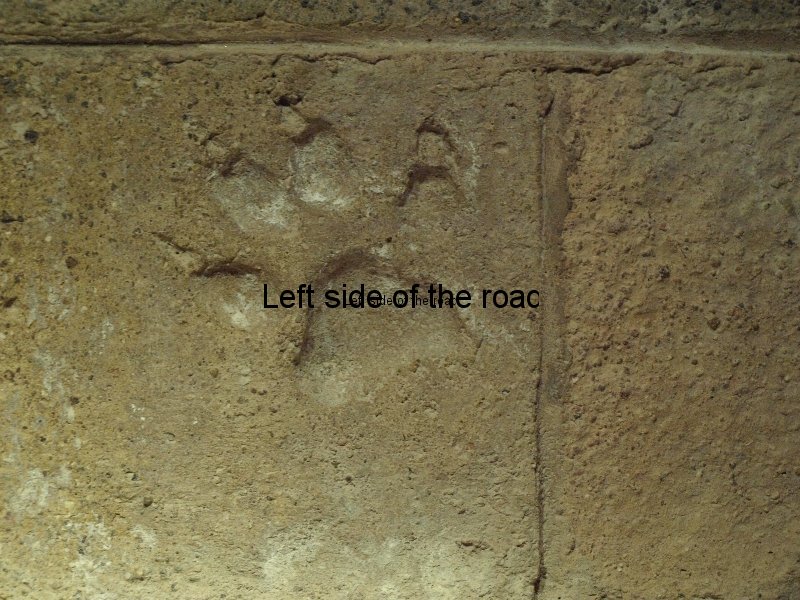

A particularly interesting story is that of the dogs that acted as virtual air raid wardens for the population. They would be able to hear the drone of the bombers coming over the sea, from the Balearic island of Mallorca, long before humans. As Pavlov suggested the dogs associated this noise with the inexplicable (to them) consequence of explosions, fire, noise, strange smells and potential death that comes with aerial bombardment.

The people of Sant Adrià suffered on two accounts. Theirs was an industrial area, and so a ‘legitimate’ target in times of war, but they were also implacable adversaries of the fascists and so had to be terrorised.

Visiting the shelter: Open the last Sunday of each month, though Jordi can be contacted, via email jvilalta.pmi@gmail.com or on +34 609 033 867, to arrange visits at other times.

For more on Memoria Democratic see: