More on the Maya

Lubaantun – Belize

Location

The ruins of this regional capital were found some 40 km from the coast, on a mountain top in the valley of the River Columbia, situated 500 m from the settlement. Various streams flow past the foot of the natural elevation and an area of tropical rainforest extends below the site. On the banks of the Columbia sits the village of San Pedro Columbia, one of the largest Maya communities in southern Belize. The Kekchi women in the region make brightly-coloured embroideries of the local wildlife, as well as other handicrafts for tourists. It has a small museum and basic rest rooms for visitors.

History of the explorations

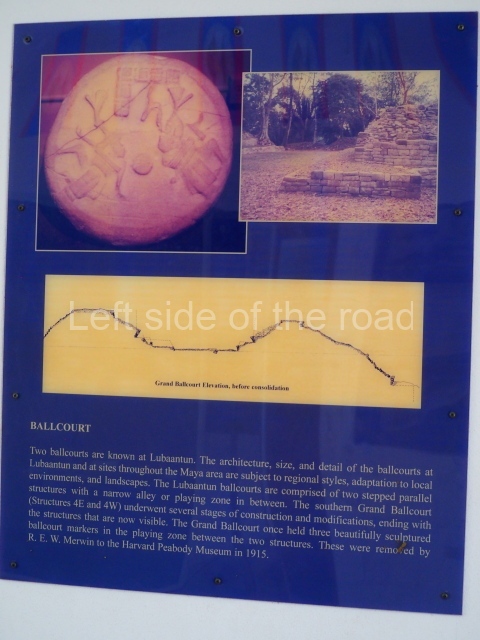

The Lubaantun site was reported in 1903 and Thomas Gann, a doctor and archaeology enthusiast, was commissioned to inspect the settlement. Gann excavated the larger constructions and his report was published in England in 1904. Later on, R E Merwin surveyed the civic-ceremonial area and drew up the first map. In his excavation of the South Ball Court, he found three cylindrical markers, the upper sections of which show two figures playing the ball game; in 1915 these were transferred to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. In 1926 the British Museum sent an expedition led by T A Joyce which was joined the following year by Eric S J Thompson, who identified several building phases in the constructions. In 1970 Norman Hammond embarked on excavations which concluded that the site was founded around the 8th century by a Cholan-speaking group – possibly the language that was spoken in the Lacandona Rainforest in Chiapas and the Peten region of Guatemala – who colonised the region to exploit the fertile land and abundant resources.

Nevertheless, their occupation of the area was short-lived – barely 150 years – as the site was abandoned around AD 890. Finally, Richard Leventhal of the State University of New York included Lubaantun in his general survey of the region aimed at establishing the type of relationship that existed between the various settlements in the Toledo district in southern Belize. A rock crystal skull was found at Lubaantun by F A Mitchell-Hedges in 1926 and is currently in the possession of his daughter Anna, who lives in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. To this day there are conflicting opinions about the authenticity of the Lubaantun crystal rock skull.

Site description

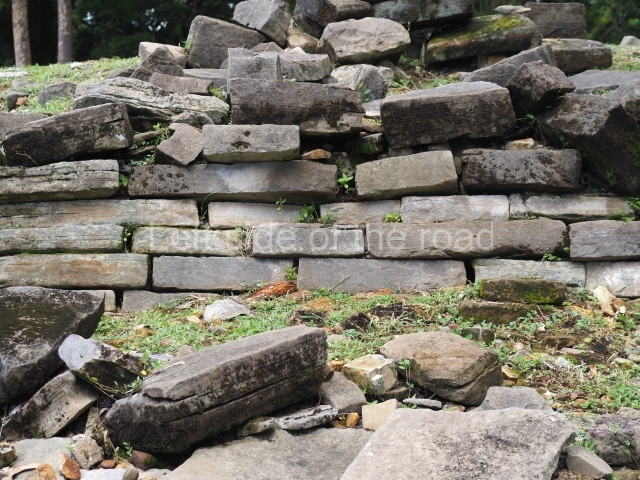

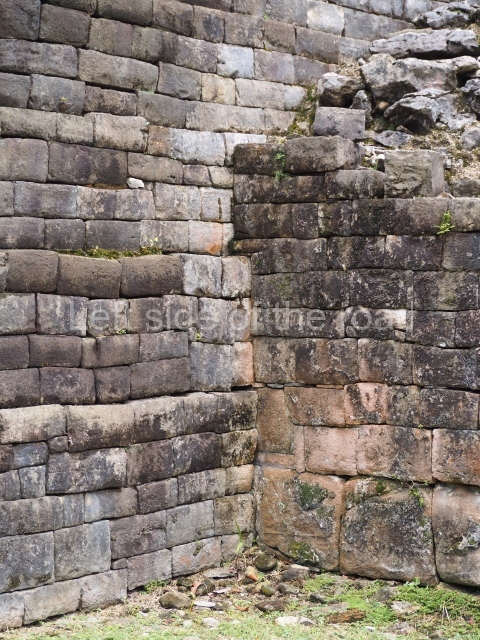

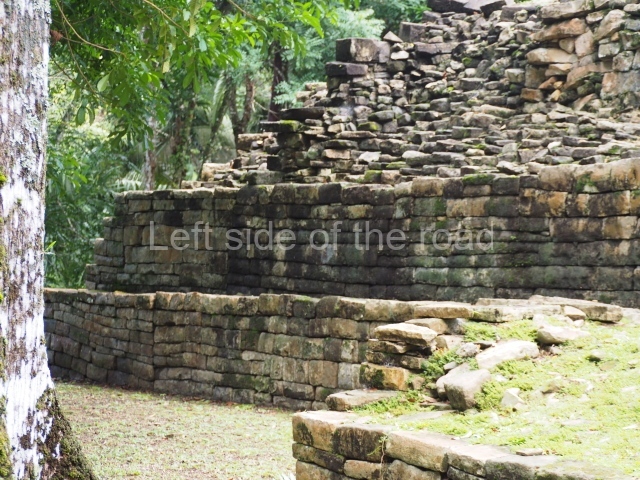

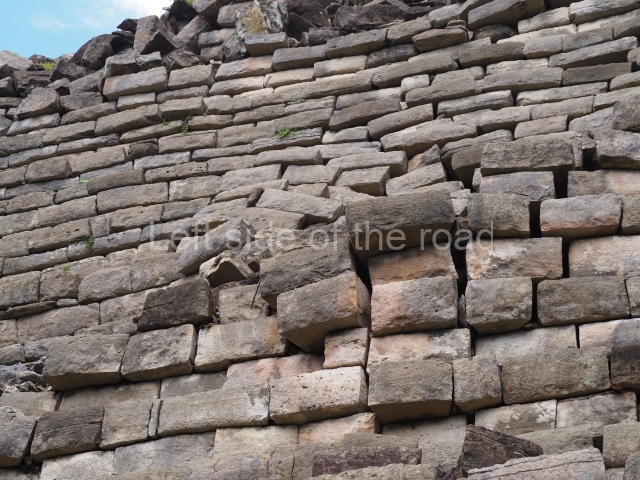

There are two unusual aspects of the Lubaantun site: it lacks the architectural decoration that is so profuse at other ruins in the central lowlands, and there are hardly any stone-carved monuments or Maya vaults. The name Lubaantun translates as ‘Place of Fallen Stones’ in the local Maya language. The site is a civic ceremonial centre from the Late Classic period. According to Jaime Awe, the archaeological evidence indicates that there were originally three concentric sections with different functions: a central area of religious constructions, a section for ceremonial buildings with ball courts, and an outlying residential area. Its most outstanding feature is that no mortar of any description was used in the constructions, each stone being carefully cut to fit the adjacent stones. The solidity of the construction lies in this method of assembly.

From the map drawn up by Hammond in 1969 it would appear that the settlement was distributed around four large plazas and three large pyramid platforms; the highest pyramid rises over 11m above the plaza and the foothills of the Maya Mountains and the coastal plain are visible from the top of it, as well as other smaller structures that may have been temples or adoratoriums. There are three ball courts, regarded as ceremonial structures; two of them lie north-west and north-east of the central plaza while the third court delimits the central area. These buildings alternate with residential platforms for the elite. It is possible to see the foundations of what may have been a steam bath situated south of the north-west ball court. Terraces and platforms were created on the slopes of the nearby hills to build residential and plaza groups. A large quantity of products were traded at the Lubaantun market: basalt and obsidian from the mountains, sea products, game and their skins, as well as farming produce – principally, maize, achiote and cacao. Maize and particularly cacao are the two products that Lubaantun is thought to have traded with other cities in the region.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp256-257.

- Plaza; 2. Ball Court; 3. Structure 10; 4. Structure 33; 5. Structure 12; 6. Plaza 4; 7. Structure 14; 8. Plaza 5.

How to get there:

From Punta Gorda. Take the bus whose advertised destination is Colombia which departs at the market end of Jose Maria Nuñoz Street. The best one to take is the 10.00 departure – there is no earlier one – as this goes by the approach road to the site. When dropped off it’s about a 1.5km walk to the site. If you take the 10.00 you will arrive at the road to the site at approximately 11.00. The bus back to Punta Gorda leaves its terminus at 12.30 and passes the approach road just before 13.00. But you could walk back along the road towards the settlement of San Pedro Colombia and go into Mag’s Cool Spot for a drink, just a few metres from the junction where the bus will turn to go to Punta Gorda. You could also have a look at the front of the church (just up the hill, on the right, in the direction Punta Gorda) to see how the stones from the Mayan site were used in the construction of the Catholic church – not an uncommon occurrence.

GPS:

16d 16’ 55” N

88d 57’ 34” W

Entrance:

B$10