Chapter 8 – Kirkby Stephen – Keld

The day of the mud

According to the guide-book this could well be the wettest day of the trip, not from the sky but underfoot. At the same time it would have to go some to beat the days when I was walking in the Lake District.

The day dawned, and remained as such for most of the day, with the same conditions I have gotten to expect. Dull, overcast, low cloud but not so low that the tops were in the mist, quite still (so there was little chance of a change) yet surprisingly warm. And dry, that is without rain. I was beginning to realise that during my time of doing this walk the prevailing weather was coming from the east and basically keeping any wet, Atlantic weather well out to sea.

After an indifferent (to say the least) breakfast I left the hostel which, so far, is the worst of the places I’ve stayed in. I’m also starting to get fed up with asking for ‘the full English’ when referring to breakfast. I need to have a fairly substantial meal at least once a day but a full fry-up ceases to have its attractions when it comes nine days in a row. Travelling away from home you tend to implicitly give up the opportunity of choice (so loved in this country at present – and against which I’m in constant battle), the variations on the theme being minimal. That growing lack of enthusiasm wasn’t helped this morning by one of the poorer offerings as the ‘main meal of the day’.

Before even leaving Kirkby Stephen I had (or more accurately wanted) to take a picture of a road sign. People who stand at the end of railway platforms and take pictures of the passing trains are looked down in our society (although it’s an innocent enough pastime) but don’t know how derisory the recording of direction signs would be considered.

But this was slightly different and there can’t be many of them in the country. These are old signs that record the distance to another town or village in miles and furlongs. Furlongs were still mentioned when I was at school but must seem as meaningful as the groat to those brought up under a metric system of calculation. For those who can’t remember, or never knew in the first place, a furlong is 220 yards, 660 feet, 40 rods or 10 chains (although we’re getting far too esoteric to talk about the last two). The furlong is a measure that developed from the strip farming of the Anglo-Saxon and mediaeval period, right up to time of early capitalist agriculture, and a hang over from feudalism. The name itself is derived from a furrow, the line of ploughed ground. Probably the only place you come across that in any regularity nowadays is in horse racing where the part miles are broken down into furlongs (I assume that’s still the case, I can’t remember the last time I watched a horse race).

And on some old road signs. I don’t know if they still exist but there was a series of books when I was younger, the ‘I spy’ series where such signs were a prize if seen on any journey. Don’t know if the series still exists, or even if there is a modern equivalent. But just in case you’ve never seen one I reproduce it below. For those in search of relics of the past it’s on the town side of the chicane controlled by traffic lights as you come into Kirkby Stephen from the west, on the same side of the road as, and just before, the Kirkby Stephen Hostel.

Although I’d taken my first scheduled rest day in Patterdale on the previous Sunday I expected to meet up with others I’d met on previous days as they were moving forward in shorter stages so today we would all come together again. I was still happy with my planned routine. But each to their own on this one. I just liked the idea of being able to wake up in the morning knowing that I didn’t have to go far. Others wanted the continuous routine, but they tended to be the ones who were only doing a section of the walk and anyone doing the full length, unless they were racing against some personal clock, would turn the challenge into a chore if they didn’t allow some sort of time off for good behaviour.

Along the route I only came into contact with one largish group who were aiming to complete the full walk, and that was a group of 9 from Leicester. Doing it for charity and sponsorship and (I later got to know) 2013 was the 8th year that the same organisation (a hospice) had arranged such a trip. They had stayed at the same place in Shap and had their own support vehicle and driver so they tended to move faster than me so I only rarely came into contact with them on the walk.

What I did learn from that minimal contact was the extra time it takes with a group. From Kirkby Stephen we left at more or less the same time and they overtook me as I was stripping off from being over-dressed due to the unexpectedly high temperature. But I soon overtook them as they were at a non-existent junction (as far as I was concerned) consulting a map. It seems they were using maps rather than one of the guide books and that seemed to be making things difficult for no real gain. I can see the idea of trying to navigate using traditional methods but I don’t think that it goes together with a long-distance walk. Some of the days were long enough without adding more time out on the hills discussing which path to take, when the guide books (at least the one I was using) gave a good field by field, gate by gate, stile by stile, description of the route. Use the two together but not just the maps. I’d already realised the advantages of travelling alone, seeing this group – who managed all the stages that they wanted – hanging around and wasting valuable minutes only convinced me more of the correctness of taking on the challenge solo.

Apart from conditions under foot this wasn’t supposed to be a particularly hard day and the greatest effort needed being the ascent to the summit of Nine Standards Rigg, which started just after leaving Kirkby Stephen. The first part of the climb takes place on a quiet country road and then a relatively wide track when the tarmac runs out. From this point it’s possible to see, in the distance, the nine stone pillars which give the hill its name.

Although wet as the path got narrower and steeper it wasn’t as bad as I’d experienced earlier in the walk and that was mainly due to the warm summer. I don’t think the summer of 2013 in the north-west was in any way exceptional, just not as bad as the ones of the recent past, and the colour of the vegetation and the amount of water in the hills seemed to confirm that up to Shap and the moors that led to Kirkby Stephen. Then we came under the influence of the east of the country and by talking to people who were local I got the impression that it had been much drier there than in the west. The streams were not as full and generally the water leaching from the hills was merely a trickle.

Although plagued by low cloud Nine Standards Rigg is only a couple of thousand feet high and was lower than summit allowing for a good view of the pillars if not with a bright background. As with most of these types of structures (and there have been an increasing number of various combinations and incidences of standing stones since leaving the Lake District behind) no-one can say definitively why or when they were constructed and allows for any explanation from the mundane to the fanciful. The mundane: boundary markers – although that’s a lot of work to established a line, especially when so close together. The fanciful: built to frighten the Scots that they would have to fight giants if they came any closer. Of the two I prefer the second.

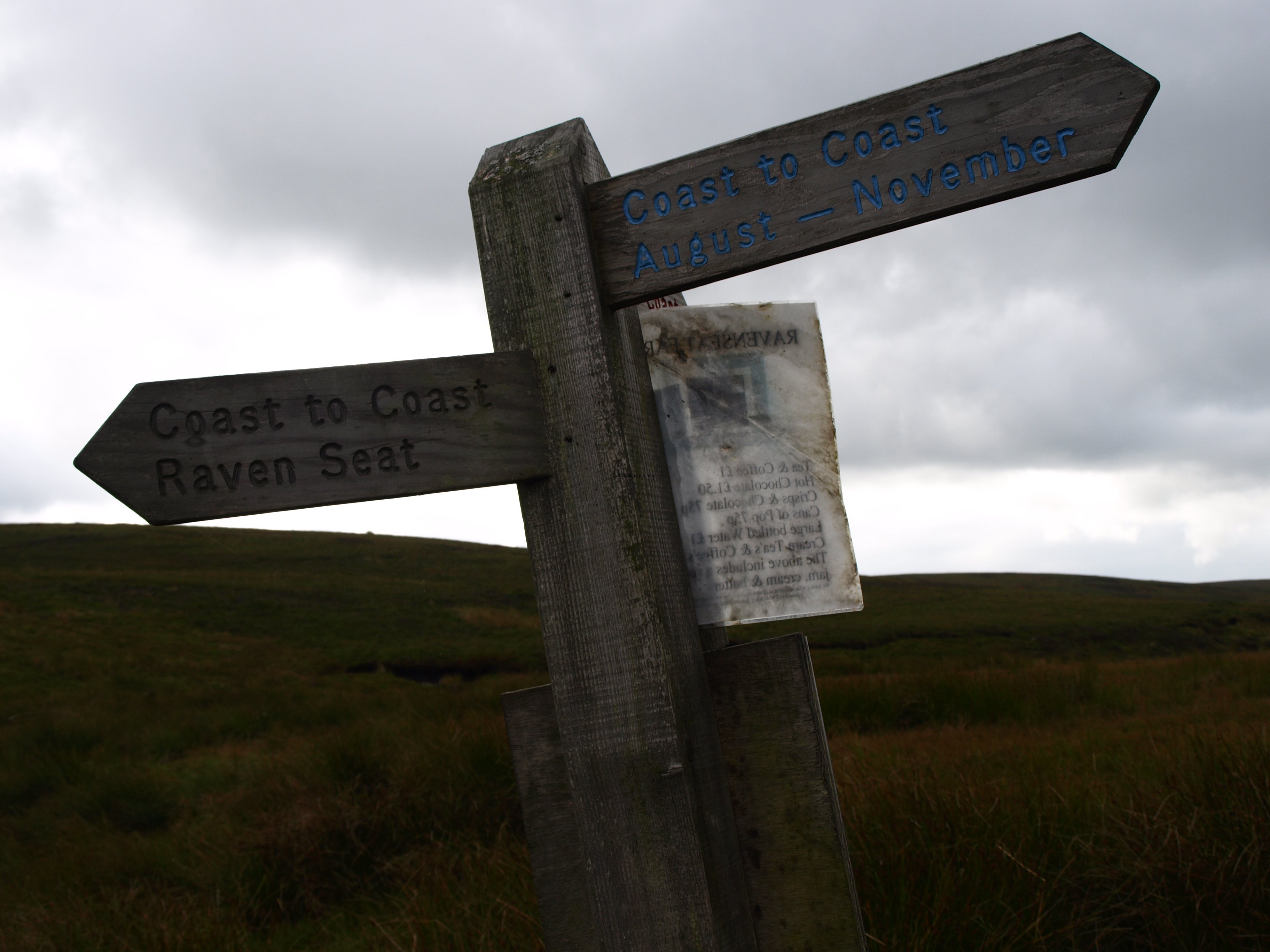

If I thought I had got away with the water before reaching the stone pillars that belief was shattered over the course of the next hour or so. This had already been signalled by the fact that there are three routes to get to the east past Nine Standards Rigg and each one is recommended at certain times of the year. This is both in an attempt to prevent erosion but also, I assume, to allow people to get through without having to swim through a sea of mud (or really liquid peat).

The route for most people this day was the Blue Route, recommended from August to November, i.e., the driest months. It’s also the most direct and maintains a high viewpoint, the best one on clear days. But it wasn’t easy by any means.

These peat moorlands are very vulnerable and once they get damaged water will start to flow through the little gullies making them wider and deeper as time goes on. Why no attempt had been made to prevent this situation from getting as bad as it is, and only getting worse in the future, is a mystery. Well, not really. It’s all about money and no government has been, and for the foreseeable future, would invest the small amount it would take to both protect and improve this piece of moorland as a public amenity. There may be unspecified billions for the controversial high-speed train line but not a few hundred thousand for such socially and ecologically beneficial projects throughout the country.

It can’t be beyond engineers to come up with a simple, long-lasting and non-invasive solution. After all in 1829 George Stephenson came up with a solution of crossing Chat Moss over which he wanted to constrict the first line between Liverpool and Manchester. This stretch of railway, still in constant use to this day, ‘floats’ on a bed of bundles of heather and branches, bound together and covered in tar and, as far as I’m aware, has never needed to be repaired since as the chemicals in the peat bog prevent the vegetation from rotting down. Surely a scaled down version of that engineering technique could easily be adapted to footpaths on the Yorkshire (as well as other) moors?

As it was the get along you had to clamber as carefully as possible down into a ditch and then get up the other side without disappearing up to your knees in mud and water. Slowly you learn that the best way to get through is to tread as softly and carefully as possible. Using the walking poles you then need to pull yourself up from the ditch, in the process trying not to put too much downward pressure on your feet – but that’s easier said than done. I think that by the time the ground became firmer as height was slowly lost I was better than I was at the beginning, nonetheless it was a stretch that required concentration and not an inconsiderable amount of effort.

I couldn’t have done that section without the poles, or at least not without arriving at the valley bottom without looking as if you had spent an active and wild afternoon in one of those god-awful mud-wrestling pubs that appeared like a plague in the 1970s. At the same time the poles only add to the problems of erosion. When you stick the tip of the pole into the ground and it sinks a couple of feet, without a great deal of effort, you can understand how fragile this terrain and environment really is. Over time, using poles to get out of these small ravines the edges will be gradually pulled away as the poles tear the structure of threads that holds the peat together. You come up with one solution but that then causes another problem!

This terrain is going to dominate second half of the journey so it will be interesting to see how it feels to be walking along the paths of these high moorland areas of Yorkshire.

For that is where I arrived this day, out of Cumbria and into Yorkshire. Getting close to the half way mark – which seems to have taken a long time to arrive – and now crossing a watershed, literally. After Nine Standards Rigg all the water that I plough through or washes over me will be heading to the North rather than the Irish Sea.

It’s a very different terrain in a number of ways. Still lots and lots of sheep but also a growing amount of farm land, both arable and livestock. But an area that has also gone though many changes over the years. On this day’s walk I became very much aware of the number of abandoned houses that line the valley – as the end of this walk, Keld, is at the beginning of the Swaledale River course. At one time many more people would have lived in this area, an area that tourists and visitors might consider idyllic but to the people who would have been forced to live there in the past the area would have been harsh and life hard – not that far from a road but still a long way anywhere of any size in terms of population. Changes in agricultural practices would have reduced the numbers working in the fields – and I don’t think I saw anyone other than another walker on the hills all day. And for the young this place would have virtually nothing to offer. Lots of good filming locations which involve isolated buildings in a dramatic environment.

The other notable event of the day, and that was very near the end as I was coming down an old farm track to the minor road running parallel to the river, was an ‘encounter’ with a dying rabbit. I haven’t seen many rabbits along the route, not least as when they are out to play I’ve either not started the walk for the day or have already finished, but the ones I had seen looked relatively healthy. The one I saw this afternoon was far from that.

I had heard or read some time ago, can’t remember when or where, that myxomatosis was still claiming victims amongst the rabbit population. This afternoon I saw first hand the consequences.

Myxomatosis was introduced, accidentally or on purpose is still open to question, into the UK in September 1953 and soon was showing what damage it could do to the rabbit population. It is estimated that by the end of 1955 95% of all rabbits were dead, a virulence that must hold some sort of record. Those that survived did so by luck and by building up resistance so in subsequent years the population has bounced back and until I heard that it was showing itself recently I had assumed that it was a thing of the past. Like smallpox in the human population, when you reach a certain level of immunity it can be considered to be no longer a problem.

Unfortunately for the rabbit this is not the case. When at school I remember reading a poem from one of the ‘modern’ poets of his reaction to walking in the countryside (it must have been 1954/5) and coming across these pathetic creatures almost rotting alive. The disease seems to one of those that basically eats away at the body until multiple organ failure leads to death. Through the wonders of the internet I’ve been able to learn that this was a poem called ‘Myxomatosis’ by Philip Larkin. I remember how shocked he was on seeing these animals in their sad state but until I caught a movement out of the corner of my eye this afternoon had never had personal experience of the issue.

This was the middle of the afternoon, about 15.00, and the rabbit was beside the path, frightened by my presence but too weak to do anything meaningful about it. I had learnt, 40 odd years ago or more recently I can’t remember, that one of the outward signs of the infection was a swelling around the eyes so was fairly certain of the cause for its distress when I saw that. Added to its sluggish movement it was covered by a small swarm of flies, starting to get their meal before the host was dead. It wouldn’t have survived the night, I’m sure, but wonder if I should have done the humane thing and put it out of its misery. I didn’t, thinking I might have regretted that more than walking on by. A distressing sight.

Strangely hare’s don’t get suffer from myxomatosis although they can be a vector as the disease is spread by fleas (in the same way that the bubonic plague was spread by fleas from rats). I’m sure the brave scientists at Porton Down would love to have discovered the secret of the selectivity of myxomatosis when they were developing their chemical and biological weaponry.

The final stretch along the road to Keld should have allowed me to witness some of the waterfalls (forces) that exist along this stretch of water but the low water levels at the time meant they were nothing like usual, the pros and cons of a dry summer and still rain free days. And it was certainly pleasant to be arriving at my overnight accommodation a good couple of hours before 18.00.

So at 15.30 on Wednesday 25th September it was 98 miles down and 102 to go

Practical Information:

Accommodation

Tel: 01748 886549

The place has a mixture of accommodation, from camping to the bunkhouse. Don’t think they do the traditional B+B. And as it says in the web address they have yurts, two of them in the entrance drive way where the camping is based.

In the bunkhouse, £21 per night per bed – with a help yourself to cereal and toast type of Continental breakfast. Will do an egg and bacon baguette in the morning for £3.50. Evening meals about £8. Has an alcohol licence but there are only cans available. Takes payment with card or cash.

(I apologise for the delay in publishing this post – after surviving the mud on Nine Standards Rigg I got caught up in a metaphorical mud.)