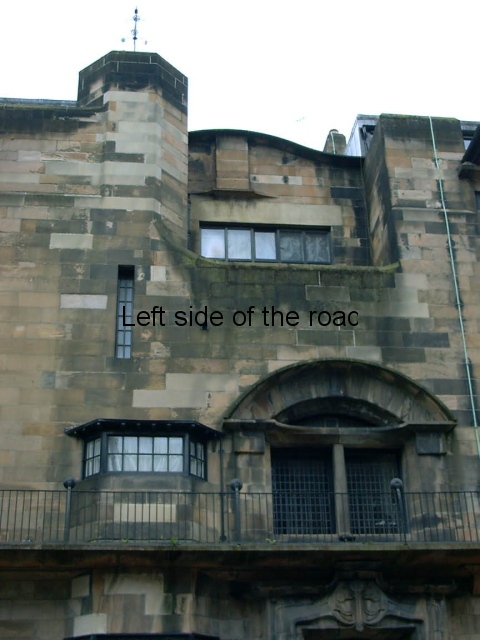

Entrance – the still not yet Burnt School

‘Burnt School’ – Mackintosh Building, Glasgow School of Art

‘To allow a building to burn down may be regarded as a misfortune; to allow it to do so twice looks like carelessness.’ (With apologies to Oscar Wilde.) But this is the situation the people of Scotland are faced with after the second, even more devastating, fire at the Mackintosh Building of the Glasgow School of Art – henceforth referred to as the Burnt School.

Before the inferno(s)

The Burnt School was designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh at the end of the 19th century. He was one of the few British artists and designers who embraced Art Nouveau which was becoming dominant in Europe at the time. (Art Deco, the British equivalent didn’t really take off until after Word War I.) Like others of that school, especially Antoni Gaudi in Catalonia, Mackintosh designed everything from the buildings themselves down to the door handles. The Mackintosh Building was built in stages but was finally completed in 1909.

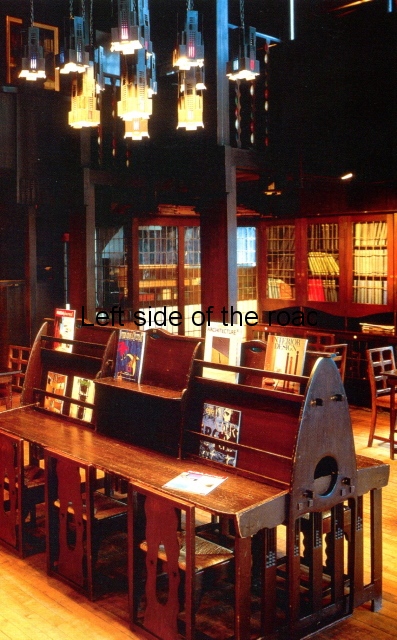

It managed to survive for just over a hundred years but in may 2014 a fire in the basement, amongst work being prepared by students for the end of year exhibition, ended up destroying a huge section of the building to the right of the main entrance – the west wing – including the very distinctive library.

Old Library – Mackintosh Building – Burnt School

I’m not aware of any real investigation into why the fire happened in the first place or why it caused so much damage. What is certain is that no lessons were learnt at all. After all it was such an ‘iconic and historic building’ there would always be public money to rebuild. Modern technology meant that the building had been surveyed and even the door handles (mentioned above) could be replaced with accurate copies. A mere £35 million contract was drawn up and the job was given to Kier Group – which had become a big player in the construction business throughout the UK.

This was in 2016 and at a time when another big player in the construction business (Carillion) was coming under scrutiny for its less than stable financial performance so some alarm bells should have been ringing.

The Second Inferno

The bells made no sound in 2016 and they didn’t on the night of 15th June 2018 either. That was when, the majority of the restoration having been completed, yet another fire broke out in the building. How long the fire had been raging before the alarm was given is unknown (there doesn’t ever seem to be any proper investigations and the apportioning of blame in these incidents) but this time it was impossible for the local Fire Brigade to bring it under control. Basically they were fighting a rear-guard action and were attempting to stop the fire from breaking out of the block where the now Burnt School was located. This meant that an old ballroom, that was being used as a large bar, and a number of shops on Sauciehall Street were allowed to burn – and are derelict to this day.

So much water was pumped into the building that the ground became saturated and the walls, that remained after all the flames had been put out, started to subside. To stabilise the now gutted structure took weeks and local residents in the immediate vicinity were denied access to their homes over that time.

Burnt School Facade – before

…. and after

(Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris benefited from the Scottish experience as the fire fighters there – in another fire that was burning longer than it should have before the alarm was raised – had learnt that too much water will bring such a major structure crashing to the ground. They followed that tactic despite the wise advice provided by Donald Trump who suggested bombing the building with water from the air – in the same way that forest fires are tackled.)

Burnt School West Wall before

…. and after

The Aftermath

What was most disturbing about the aftermath of the fire – before any ‘investigation’ of why it was allowed to happen in the first place – was the mad rush by so many individuals, including the Directors of the Art School and top Scottish politicians, to pledge that the phoenix would rise from the ashes. They made these statements as if it were a given. Even while the smoke was still rising from the rubble the figure of (yet another ‘mere’) £100 million was being suggested as the re-build price. Anyone who has followed such estimates in the past on many projects throughout the UK would doubt whether the final price would be at that ‘low’ level. Such schemes tend to go two, three or even more times over the original budget.

It was just assumed by this artistic and political ‘elite’ that the public purse would cough up to provide a spanking new reproduction of a 110 year old building and place it in the hands, and under the control, of a group of people who had shown themselves totally inept in looking after what was part of the Scottish National Heritage. You wouldn’t put them in charge of a Wendy house let alone something so valuable.

If there’s such a lot of money sloshing around why isn’t it being used for more important, crucial and socially valuable projects. Glasgow is far from being the wealthiest part of the UK and although there are wealthy people there is an awful lot of deprivation and squalor – even close by the Burnt School.

Soon after the second fire local people, including community groups and local politicians, started to ask if the money couldn’t be better spent. A report from the Culture Committee of the Scottish Parliament (in March 2019) stated that the Burnt School Directors had shown complete disregard to safety procedures and a cavalier attitude towards looking after the building – just assuming someone would be prepared to sign a blank cheque.

Now opportunist politicians, like Nicola Sturgeon, remain quiet after they had been able to shine as concerned under the limelight in the days after the fire. As in Paris there are always those who spout off about what will happen but become quite and slink back into the shadows when they realise that they might have made promises they won’t be able to keep.

Even if you look at the official website of the Burnt School you will find that they seem to think history stopped in the days before Fire No. 2. They report on ‘progress’ up to the early part of 2018 but ignore the present day reality.

As I was checking my information for this post I came across a statement which I found amusing – but also one that asks more questions than it answers. On 29th June 2018 Kier were taken off the contract. Not surprising as (together with the management of the Art School) they were significantly responsible for what happened that Friday night a couple of weeks before. However, I’ve been unable to find out how much Kier had been paid for the work they had completed up to the 15th June 2018. Presumably they didn’t have to wait until the end of the project before cheques started going into their account. Now that all that work has come to nought should they be paying back what they have already been given? After all they have failed to live up to the conditions of the contract.

Kier is presently ‘in difficulty’ financially, seemingly having followed a similar pattern to Carillion and overstepping themselves. Their responsibility for the fire at the Burnt School might not be the cause but it wouldn’t have helped their current situation. Would you give them a contract for your home?

Another aspect which involves finance is the fact that the Scottish Parliament has compensated those other business in Sauchiehall Street, and some of the nearby residents, for the losses and disruption they have incurred in the last year or so. That money again comes out of the public purse. As with the disaster of the fire in the Grenfell Tower in London two years ago private companies make a cock-up but it is the State that has to pay for the consequences. In London that is amounting to hundreds of millions of pounds and the issue still hasn’t been resolved. What will be the figure in Glasgow?

So that’s the situation in July 2019. The future restoration of the building is certainly not certain and it will probably be sometime before the final decision is made.

The Future?

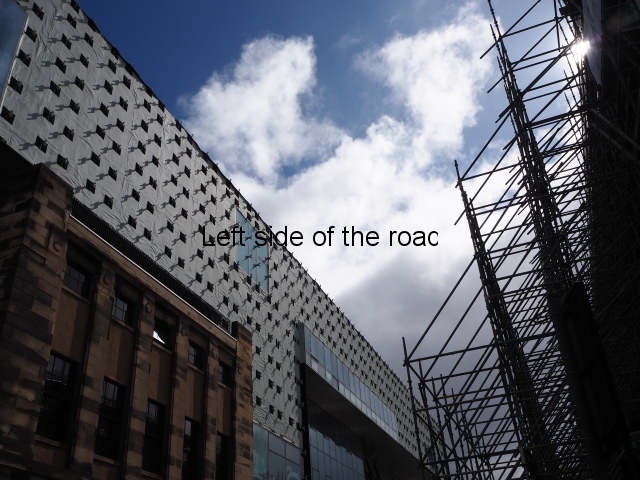

Now I want to discuss scaffolding.

One of the ‘positives’ of the fire is the amazing structure that surrounds the Burnt School. I’ve only seen the outside but I assume that there must be something similar on the inside of the ruin.

But what can be seen is truly remarkable. That single building must be using virtually all the scaffolding that was in Glasgow and the immediate surrounding area. I have never seen such a complex pattern of scaffolding. The sheer quantity, in such a relatively small space, is mind-boggling.

The owners of scaffolding companies in Scotland must have, figuratively, warmed their hands on the flames of that fire. What they are charging for all this work will keep them in champagne and caviar for a long time on their world cruises. And the actual scaffolders who climbed and created the structure must be glad that Glasgow has so many incompetents in charge of such heritage buildings. In any other circumstance the bulldozers and wrecking balls would have been in within hours and by now the plot of land would be empty, ready for yet another speculative complex that Glasgow doesn’t really need. As it is the scaffolding will be there for years.

But it’s a work of art in itself. It is both aesthetically pleasing as well as being a bit of an engineering masterpiece. It must have been a challenge which no scaffolder had ever encountered in the past. And to keep the place ‘safe’ in the present and for the near future they had to go really far back in the past. The way the scaffolding is constructed, especially on the east side, is reminiscent of the wall of a mediaeval Cathedral, with its buttresses spreading out at the lower levels.

Burnt School – east wall

I think it’s an artistic wonder in its own way. My suggestion is that they get rid of any of the stone that still hasn’t fallen, or been cracked by the heat after having been dowsed with cold water, so the area is safe and then turn the area and scaffolding into a tourist attraction.

Children could practice their climbing skills. Artists from around the world who have a history of covering mountains and other large structures in coloured plastic could be invited to create temporary installations, perhaps with light and sound shows at night. That would attract even more people than used to visit the Burnt School before it was burnt.

The scaffolding should be bought and that would save a fortune. Such an approach would cost much less than the estimated £100 million and might make people think more seriously about what they have and, hopefully, make them more careful not to lose it through their carelessness.

Future generations would then be able to wonder at the foolishness of mankind and the destruction created as well as the ingenuity of others in trying to mitigate those disasters.

‘Burnt School’ – Mackintosh Building, Glasgow School of Art – Part 2