Ypres, in south-west Belgium, was totally destroyed between 1914 and 1918 being, as it was, the area on the Western Front, known then as the Ypres Salient, that the British Army would never concede to the German forces, whatever the cost in human life. Now the rebuilt town lives on that destruction.

Thousands of visitors go there every year in order to remember, commemorate and mourn over the useless sacrifice of so many (mainly) young men from whatever country involved in the conflict. Those 4 years of slaughter are shamefully described by the British as the ‘Great War’, known in history as the First World War, but really is another example of where the working class fight out the disputes between the rich. Commemoration of those killing years only makes sense if that war really was (as it was ‘advertised’ and propagandised at the time) the ‘War to End All Wars’ if, indeed, 1918 saw the end of the useless and wasteful slaughter of lives that is an integral part of the capitalist and imperialist system.

But instead of being the end of the history of war this ‘Great War’ only presaged a century of even more destructive and murderous conflicts.

Ypres was in the wrong place at the wrong time. So it had to be destroyed. Not by design but just because it was there. It’s history stretching back almost a thousand years meant for nothing to the heavy artillery of the Kaiser’s army and the ruins of the fleeing residents homes’ became the brothels for the soldiers of the British Empire, seeking solace and relief from the horrors of the front.

Many of them returned home to a ‘land fit for heroes’ where they were ignored by the state that had sent them to Flanders Fields in the first pace and for a future that offered less as time advanced to an even more destructive conflict that would see the death of many millions of lives that made WWI seem like a picnic in comparison.

In Ypres the Gothic Lakenhalle (Cloth Hall), originally built in the 13th century, was reduced to a huge pile of rubble by German artillery fire, as was the nearby St Martin’s Cathedral. Both have now been rebuilt, perhaps in an effort to try to convince the population the past had not really happened and the good times could return. This falsification of the past has obvious negative effects as even some present day visitors don’t seem (as can be seen in TripAdvisor reviews, for example) to understand that the city is not as old as it looks.

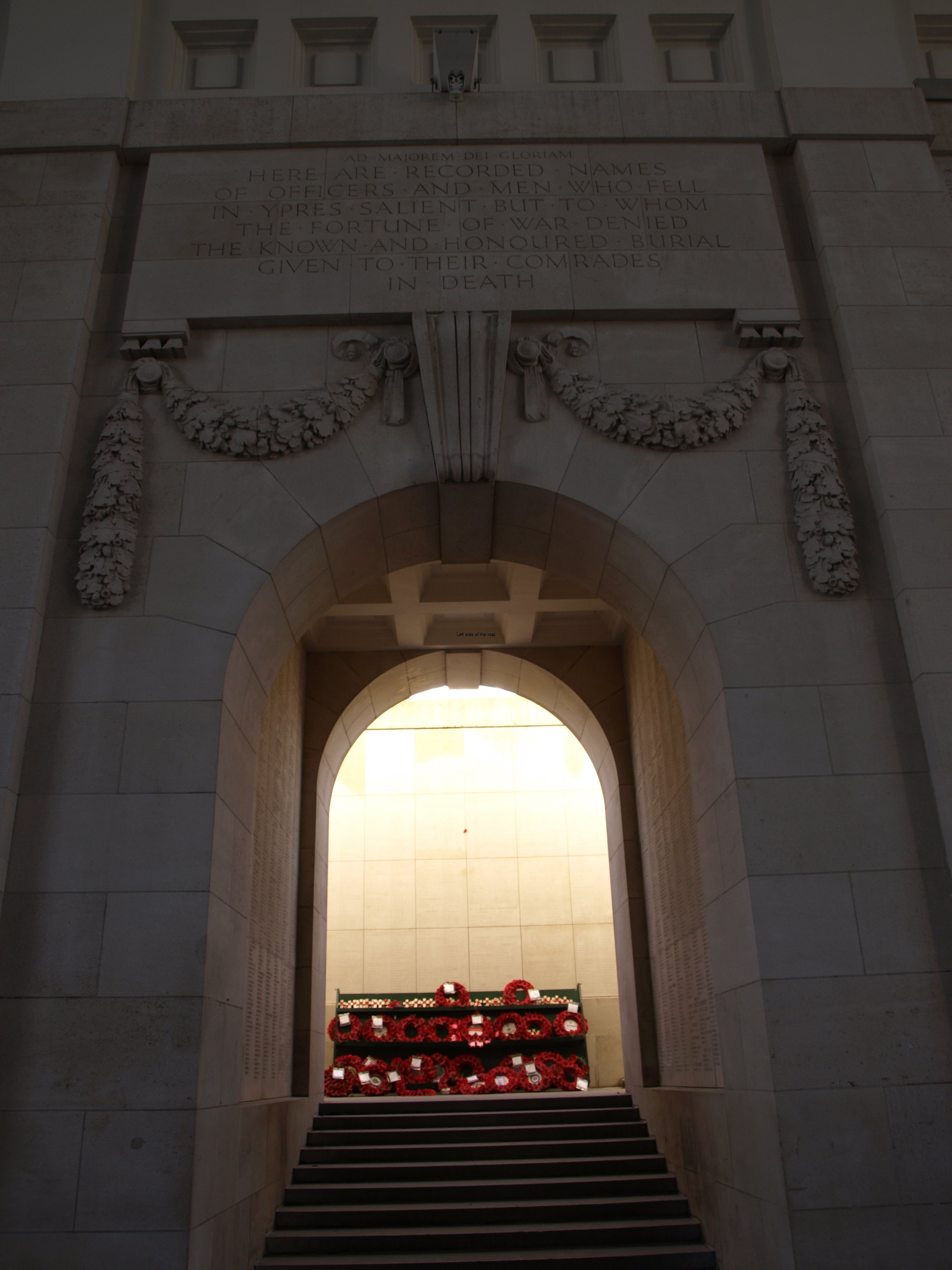

Even though that anti working class, neo-Fascist, staunch champion of the rich and privileged Winston Churchill wanted the town of Ypres to be turned into a memorial to the British dead the Belgians were able to get their homes back as long as they allowed the British imperialists to build a memorial arch that fitted in with their perception of Imperial splendour. The result is the Menin Gate, at the north-eastern end of the town’s principal (reconstructed) thoroughfare.

Officially unveiled on July 24th 1927 this monument records the more than 54,000 combatants of the British Empire (later to become the Commonwealth) who have no known grave. These monuments are always emotional – you can’t help but think of the useless waste of life for something so lacking in substance and relevance to those who actually did the dying. On both sides of the arch facing the road that passes beneath are two carvings that maintain that those who died did so ‘Pro Patria’ – For Country – and ‘Pro Rege’ – For King. Not for themselves, their families, their class but for a bunch of parasitical aristocrats who use tradition and so-called ‘loyalty to the Crown’ to keep the forelock-tuggers in their place.

I remember a couple of years ago listening to a Radio 4 play where one of the characters stated that he understood why the ruling class sent its sons to die in the trenches but not why the industrial and agricultural families gave white feathers to their sons if they didn’t rush to volunteer to suffer in the mud of Flanders fields. I still don’t understand why the working class are so keen to see their children eaten up by what is now known as the military-industrial complex.

And that’s what makes a visit to Ypres, and the memorials that litter Flanders, such a contradictory experience. Yes, you feel for the young men torn from their homes in the countryside or the industrial centres of their homeland. Here I draw no distinction between any of the ‘sides’ in the First World War – a distinction that has to be made in World War One – Part Two, that started in 1939 (at least in Europe) to kill and be killed by their international brothers. They died needlessly but there was a general perception amongst the populace that such a war was so destructive, so ludicrous, so meaningless, so wasteful, that such could never happen again.

But here we are, in 2013 on the eve of the centenary of the outbreak of the ‘Great War’ and Britain has been involved in one of the longest wars in its modern history where an unrecorded number of dead (residents of the invaded country) number in their hundreds of thousands – but they really don’t count as they are Iraqis, Afghans or Libyans.

The Last Post ceremony that takes place EVERY day at 20.00 is an even more disgraceful for that reason. As are the ceremonies that take place every year at 11.00 on November 11th. If other wars, with the same rationale, that is the perpetration of the rule of one class over another, as was the case in Greece, Malaya, Korea, Vietnam to mention only a few, continue to take place (with our connivance or acceptance) then nothing has been learnt and the celebration of the dead of the Ypres Salient becomes a sham, if not worse, an insult to those whose disappeared under the sticky Belgian mud – good for leeks but a killer for northern factory hands.

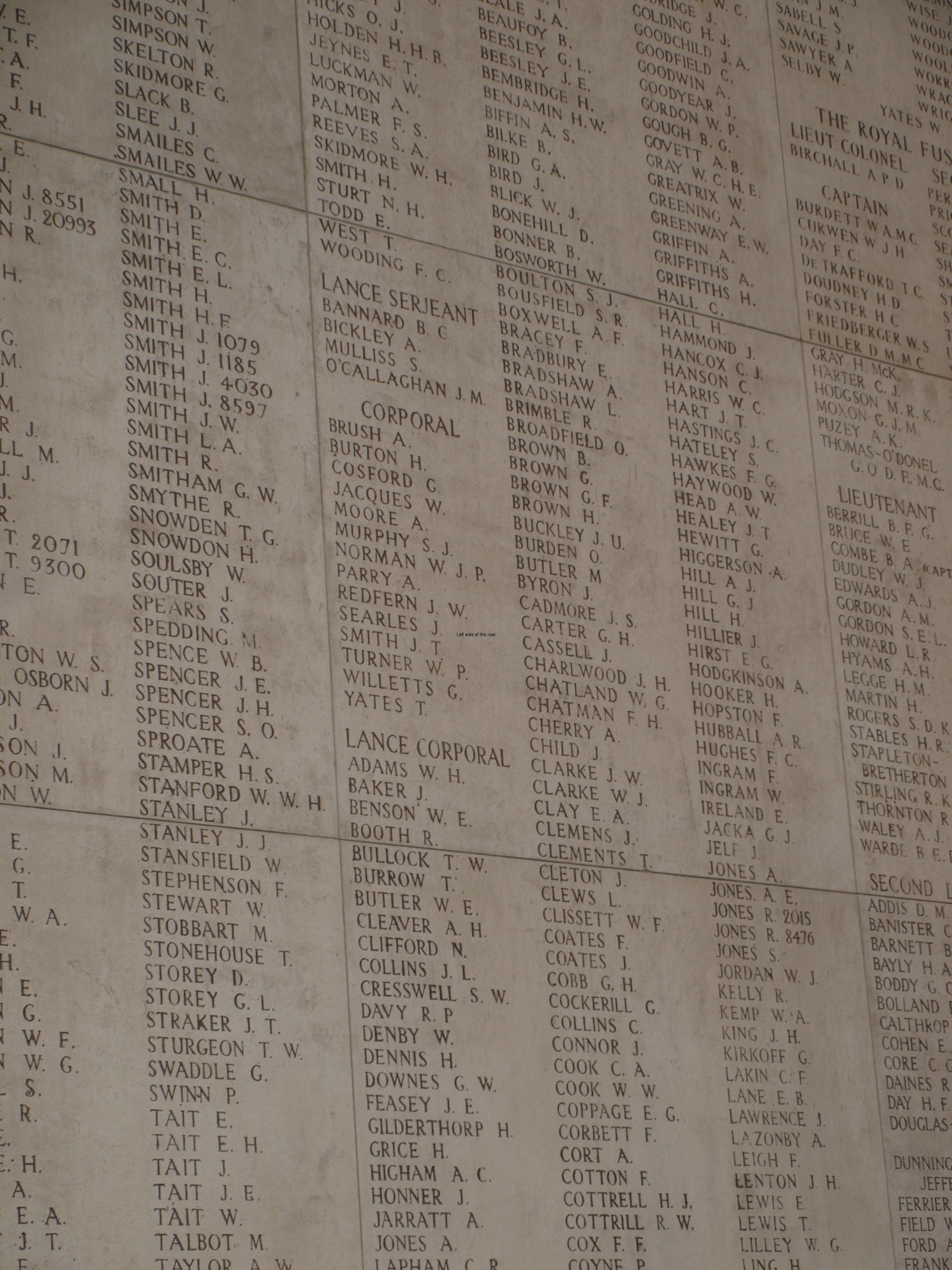

The class nature of the war is even demonstrated by the way that the names of the dead are recorded. It is not the individual who is commemorated but his rank, each name coming in descending order depending upon the insignia on their uniform. This is a situation where the last continue to be the last as the ordinary private foot soldier is the last to be recognised in his regiment’s roll of honour.

Big as it is the Menin Gate is not big enough to hold the names of all those who have no known grave. For that reason another monument in the Ypres area was constructed at the Tyne Cot Cemetery, just to the south of Passendale (about 8 kilometres to the north-east of Ypres).

Here another 35,000 names of those who became manure for the farms that were re-established in the years after the slaughter can be found.

Tyne Cot is a ‘typical’ First World War cemetery, with its serried ranks of white marble headstones, some of which have a name, many of which don’t. It’s also the biggest cemetery of the ‘Empire’ dead and therefore has the most visitors from the 21st century. If you are buried in one of the smaller cemeteries that abound in this region only aficionados of the war, obsessed ex-servicemen/women or ghouls will pass by your last resting place.

If a war memorial such as the Menin Gate which lists thousands of names is emotional that takes a step up when you see these rows upon rows of headstones. Carefully carved with the insignia of their regiments and their names, rank, age and date of death (if known) most of these men had more time, effort and money spent on their deaths than on their lives.

This is the sort of place that the present UK warmongering Prime Minster hopes to send schoolchildren next year. Bored out of their minds, but glad to be away from home with their mates, what will they learn about that war? That it was the valiant British fighting against the evil Hun? That they died fighting for freedom – but for whose freedom, that of the poor or of the rich? That those from the colonies were there because they believed in the glory of the British Empire? That they thought that, should they survive, they would return to a better life in Britain? That they would return as heroes? That they would be respected as people and not as the dross of society, that many of them would have been considered coming from an unskilled background?

That they came back realising that once they had ‘seen Paree’ they could do anything? That they returned home with their weapons and organisation to see off for good their oppressors and exploiters, as their international comrades of the Russian army did in consigning Tsardom to the dustbin of history? Unfortunately not.

They returned to the same lies they, and their ancestors, had been told for generations and for the same reason we are still sending out young men (and now women) into battle situations. (The only truly ‘honourable’ war in history was that fought against German and Japanese Fascism – and the result of that war, at least in the UK, was the welfare state, not socialism but a considerable improvement to that which the 1914/18 heroes returned.)

Those lies haven’t change substantially so we are caught up in this seemingly never-ending trawl of death. Young men and women looking for an escape from the banality of modern-day society, with its emphasis on mindless consumerism and excess in everything are looking to the ‘excitement’ of warfare. In battle they can test themselves, feel real, feel ‘free’ – even when under the orders of those above them, have individuality even when the armed services by definition deny such individuality, find a meaning in life away from the debt ridden hedonism that continues in Britain even after the crisis/crash of 2008.

But many of them are now coming back home as screwed up psychologically as they did a hundred years ago (although I have less sympathy for those who join a volunteer army as it is today than those who were conscripted between 1914 and 1918). At the beginning of the 20th century most people weren’t aware of what war really meant but there’s no excuse nowadays – if you don’t watch the news then fictional films give some idea of what being shot entails. It hurts if the bullet hits you so why should it be any different for the ‘other side’? What makes present day wars more ‘acceptable’ is the advance in protective body armour and the ability to get the injured out of the combat zone within minutes and a medical infrastructure which can prevent death.

In this way modern armies end up ‘shooting themselves in the foot’. The more they protect their soldiers from death the more they create an army of seriously maimed. Just look at the images from the Vietnam war and you’ll see American conscripts going into combat zones with no more protection that a cotton shirt. Now they are more like the knights in shining armour of the age of chivalry. If their protection is greater this reduces the headline figure of fatalities but results in a greater number of seriously injured who survive, many with disabilities which will need a lifetime of support. This creates a virtual ‘hidden army’ of wounded. Some people might be able to tell you the number of killed in Afghanistan and Iraq – but the number of wounded?

In Ypres and Passendale (and, of course, the notorious Somme – but they were French so they don’t really count) your chances of survival if injured were drastically reduced, hence the thousands of names of those who lingered to death in a septic, stinking bomb crater, eaten by rats who took away their identities as well as their bodies. That’s why different headstones at Tyne Cot show no name, but perhaps a regiment, an occupation, a reason for being on the battlefront.

The returning heroes today, the ‘lucky’ ones, might have got a ‘Royal’ Wootton Bassett welcome back to the UK, in a flag draped coffin, weeping ghouls lining the street, a funeral procession formally reserved for the ‘great and the good’ – but hated by the army hierarchy and government as this turned war into a sentimental exercise.

But no more.

Wootton Bassett has become ‘Royal’ but the dead of any present and future war will have to come back in the cargo hold of an RAF transport plane and think themselves lucky if there are family members to greet them.

The fate of those involved in the war of 1914-18 was different. The state didn’t really want to know about the dead, they had done their job and that was it. However, there was still a class bias to the aftermath of the ‘Great War’. Haig didn’t like, and wasn’t liked by, Lloyd George but he still got an earldom and a not insubstantial cash payment. On the other hand family members of the ‘disappeared’ had to pay French and Belgian workers to dig up the remains of their fathers/sons/brothers etc. who had been identified. This financial burden upon people who had little extra after their own daily maintenance probably accounted for the hundreds of thousands who had a grave only ‘Known unto God’ – the most common inscription in the cemeteries in the environs of Ypres.

There was a reason to create these iconic cemeteries in the 1920s. The establishment had to be seen to be recognising the sacrifices of ordinary working men without accepting any real change in the structure of society. Winston Churchill who had been in government roles both before and after the war had sent the warship HMS Antrim up the Mersey to intimidate the transport strikers in 1911 and was equally willing to use the army against workers in the General Strike of 1926.

This isn’t happening now and won’t in the future. It’s bad PR to be confronted with a mass of white headstones. People could get too emotional. It’s doubtful the dead in the 21st century conflicts (so far) will have a separate national memorial. It’s bad enough that small memorials are sprouting up around First World War cenotaphs, a national war dead cemetery is going too far.