Las Malvinas and Rio Gallegos

The Background

It would be impossible for a Britisher to make a visit to Argentina and not make reference to the war between the United Kingdom and Argentina over the Islas Malvinas, from April 2nd to June 14th 1982. That tacky,wasteful and unnecessary war was a God-given opportunity for a weak and pathetic government to try to divert the attention of the population from its failed economy and worsening social conditions. If true justice existed in the world that neo-fascist would be charged in the international court for war crimes. Margaret Thatcher was lucky. ‘Her’ side won – and so she was able to hide behind the ‘joy and enthusiasm’ of victory. After all, it’s the victors who write the history of any conflict.

The ‘other side’ was led by an equally weak and pathetic leader, Leopoldo Galtieri, a fascist army general who was the last President during the period of military dictatorship from 1976-83. H hoped to use nationalist feelings over the Islas Malvinas to divert attention away from the growing opposition to military rule. He gambled – and lost.

I won’t go into my thoughts too deeply about that shameful war. Suffice it to say that if Galtieri had held back for a couple of months the outcome could have been very different – for the history of the Malvinas as well as for the subsequent history of the two countries concerned.

At least the Argentinians knew where the Malvinas were. Most Britishers, waking up to the news on Friday 3rd April 1982 thought the Argentinians were off the north west coast of Scotland.

The British success –which was as close to a near thing as the Battle of Waterloo –meant that the military dictatorship in Argentina had just over a year before it was replaced by a ‘democratic’ government.

The war and the eventual re-raising of the Union Flag in Port Stanley released a flood of patriotism, jingoism and racism in Britain unknown since the Relief of Mafeking in 1900. In return for their stupidity the British people had the pleasure of Thatcher as their leader for another eight years, the entrenchment of the ‘neo-liberal’ economic theories(adopted, more or less, by all political parties in the UK since),the weakening of the economy and the power of workers to determine their own futures and the worsening conditions for society in general under the banner of ‘austerity’ .

The Rio Gallegos ‘Monument to the Fallen in the Malvinas War’

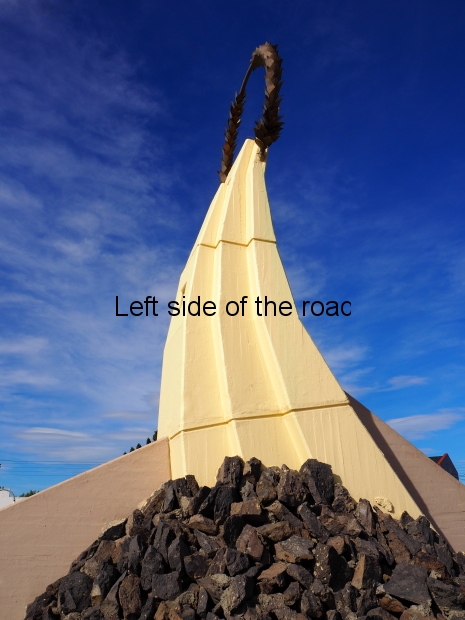

Being one of the closest points on the Argentinian mainland to the islands Rio Gallegos was obviously to play a major role in the land, sea and air war. For that reason there’s a large monument to the fallen on the outskirts of the town. Not the best of locations, to my mind, but then perhaps there’s always a different mindset when a monument commemorates a victory or a defeat.

(The monument in Puerto Madryn is on the edge of town and the one in Buenos Aires,although central, is still in a peripheral location. The ‘eternal flame’ at that monument wasn’t so eternal during the lock-down of the G-20 2018 as it was surrounded by metal crash barriers.)

I also don’t think it’s a particularly impressive monument – taking into account the feelings that all Argentinians I’ve met have towards the Malvinas. Not only is it unimpressive as a piece of architecture it doesn’t help that it’s starting to look a little bit neglected. If I read the situation correctly it was originally planned to have an almost permanent flow of water, uniting the tower to the geometric representation of the islands a few metres away. When everything is dry and rubbish is starting to collect then the original idea is not only lost it becomes an indication of lack of care.

Looking at the memorial from what would be the principle approach the entrance is flanked by two eternal flames (gas operated) which sit upon truncated pyramids.The central monument is a yellow column sitting upon a pile of rocks(presumably representing the islands themselves). From the eternal flames this column shows three levels which reduce in height and width. I’ve no idea what this implies. A short distance from the top of the column a circular crown of laurel leaves forms vertically to achieve the highest point of the monument.

From the front it looks like a vertical pillar but from the sides it can be seen that it folds back on itself, as in a concave image. Almost exactly in the centre is a small, square hole. I can’t see what this signifies but if my idea is that this monument is also a water feature it is from this hole that the water would fall towards the islands at the back of the column.

From behind the column a chute comes down steeply from the hole. This is painted red, as is the pavement on either side of the channel that leads to the pool in which sits a very rough geometric representation of the islands. I’d forgotten how complex the islands are with its coves and bays.

We get the idea that these are islands in a sea as the land is grassed over to differentiate the concrete from the water. There are no trees represented as we know from 1982 that no trees grow on the islands.

My interpretation here is that the blood of the Argentinians, in some ways, nurture the islands. That the ‘sacrifice’ of the 649 in 1982 are what make the islands part of the country. But as I’ve already said, the fact that no water is running and the area is starting to look neglected, this idea loses a lot of its power.

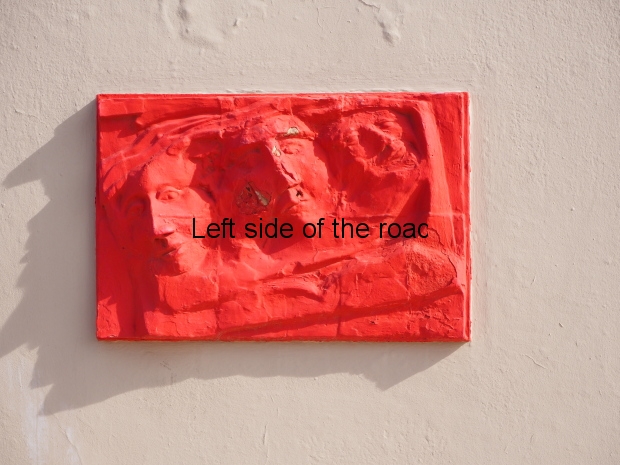

On either side of the principal monument are two, L-shaped alcoves. On the external sides there are two bas reliefs in red, of the four only one of them is recognisable and that seems to be faces in some sort of agony. Time and/or vandalism has degraded the other three. On the interior of these alcoves are fixed a number of brass or ceramic plaques that have been fixed there over a period of time by different groups commemorating specific anniversaries – this is a common approach to monuments throughout Argentina and can be seen, for example, on the San Martin monument in the square that bears his name only a few blocks away in the centre of town.

To the left of the two eternal flames is a board contains a poem written for the inauguration of the monument – I didn’t see any date of its inauguration nor any details of the architect/artist.

My translation of that poem is:

I have seen emerge, from the very soul of our land, valiant combatants of the air, sea and land parading their laurels in the infinite heaven

I have seen the sacrifice of their spilt blood bathing our islands in honour

Justice will come then, as hot firebrands engrave the memory of the men to which this symbol in concrete pays homage

Hector Pedraza

The Malvinas remembered in the port of Rio Gallegos

I’ve come across a number of murals in my travels but, due to only catching a glimpse of them from a bus window, I have no actual record of them. However, the general point is that a) Las Malvinas son Argentinas and b) those who died should not be forgotten.

In the port area of Rio Gallegos I came across these murals.

I’ll let these pictures (in the main) – with the relevant translations – make their own point.

The young soldier,converted into an angel, flying over the graves of his fallen comrades, with the ‘Sun of May’ in the top left – on his way to heaven. Notice the beatific smile on his face, as if he is the modern day version of a Christian martyr. All this image needs is the image of a Gurkha’s khukuri that slit his throat to be floating in the air behind him. This is, without a shadow of a doubt, the most bizarre and, in many ways, most unpleasant call for the dead to be remembered I have seen.

649 – they will always be our heroes (649 is the number of the Argentinian dead)

Malvinas Forever –’Old Lady (Grandma), don’t mourn that I’m with my fallen comrades on the islands. All I need is that my country remembers me.’

Here there’s no surrender. Shit! Long Live the Country (Argentina). Our own strength.

28 Heart – We will build together

This one is a little bit complicated and has to be de-constructed.

I think that the image of the islands and the soldier, with the Argentinian flag in the centre, was the original image – without words.

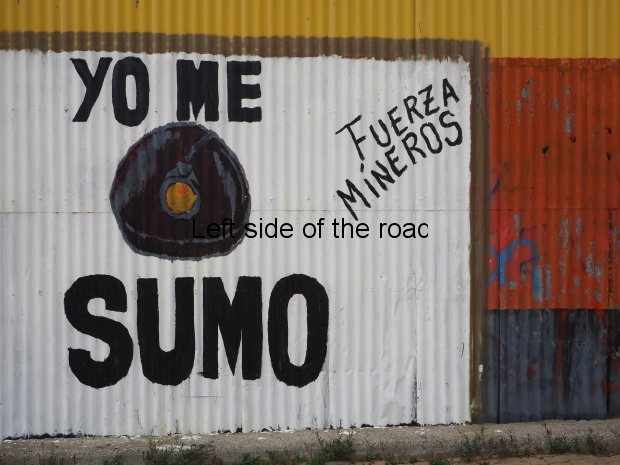

However, time moves on and other struggles come to the fore. Beside this image of the Malvinas was another which puts the case for the miners of the RioTurbio region (which used to send shipments of coal to the port of Rio Gallegos) who are under threat of closure. It depicts a black miner’s helmet with the torch attached with the words ‘I’m here as well’ and ‘Miner’s Power’. As in Britain in the 1980s the closure of the mines doesn’t just mean the loss of jobs it means the total destruction of a community.

The interpretation I have learnt from speaking to people locally is that the miners (or apolitical faction from that community) have put their slogan over the original Malvinas image to equate the two struggles that people believe in, fervently, in this part of Argentina.

(Anyone aware of the situation in Britain with the neo-fascist Thatcher and her government’s struggle against the miners in the Great Strike of 1984-5 might think that this situation in 2018 is quite ironic. It also indicates that if workers don’t start to think in an international manner and remain parochial then what effects workers in one part of the world will eventually effect all in time.)

There’s also a very small museum in Rio Gallegos dedicated to the War in the Malvinas which I will post separately.

Your first mural illustrated is indeed grotesque – what makes it so is the children’s comic idiom in which the soldier is (not very expertly) drawn. What does this say about the mindset of the artist? Gross sentimentality, perhaps, but certainly not the thoughtful dignity with which the 649 deserve to be remembered. That said, this particular area of the country seems well short of good street artists – none of the murals shown is especially well executed, the soldier-grandma image desperately short of artistry. Perhaps the best is the simplest – the “649, siempre eran nuestros heros” image. (I’m surprised that the Spanish plural is “heroes” rather than “heros”, but then again my Spanish never progressed beyond O level.)

It’s regrettable that the memorial is poorly maintained, but as you imply, it seems to be trying to say too much at once. The backwards tilt of the main element is intended, I suggest, to reflect agony (a soldier shot while advancing into enemy fire, perhaps). I can’t make much of the rest.